MITLA: Lessons From The Oaxacan Valley

Mitla is a Zapotecan archaeological site that lies in the Oaxacan Valley about 40 km outside of the city of Oaxaca. Mitla, or Mictlan in náhuatl meaning “place of the dead,” is believed to have been where ceremonial burial rites along with burials for royal Zapotecan families took place. The site is most famous for the intricate stonework that adorns several of the buildings in the complex and neighboring sites.

The story of how I learned about this place goes back to my time in graduate school where I witnessed a work of art done in masonry on my campus. That encounter propelled my interest in the craft, and I began to study masonry work in greater detail. It wasn’t until many years later that I learned the inspiration for that work of art was the architecture of Mitla.

I begin attending graduate school in Cambridge, Massachusetts in August of 2008. I lived in a dormitory near Harkness Commons, the law school student center designed by Walter Gropius and his firm The Architects Collaborative. The building was the first endorsement of modern architecture by a major university and contains many works by pioneering artists, friends of the architect. The work that seemed most interesting to me was a brick screen wall entitled “America” by Josef Albers. It amazed me how so much expression could be put into such a common building material.

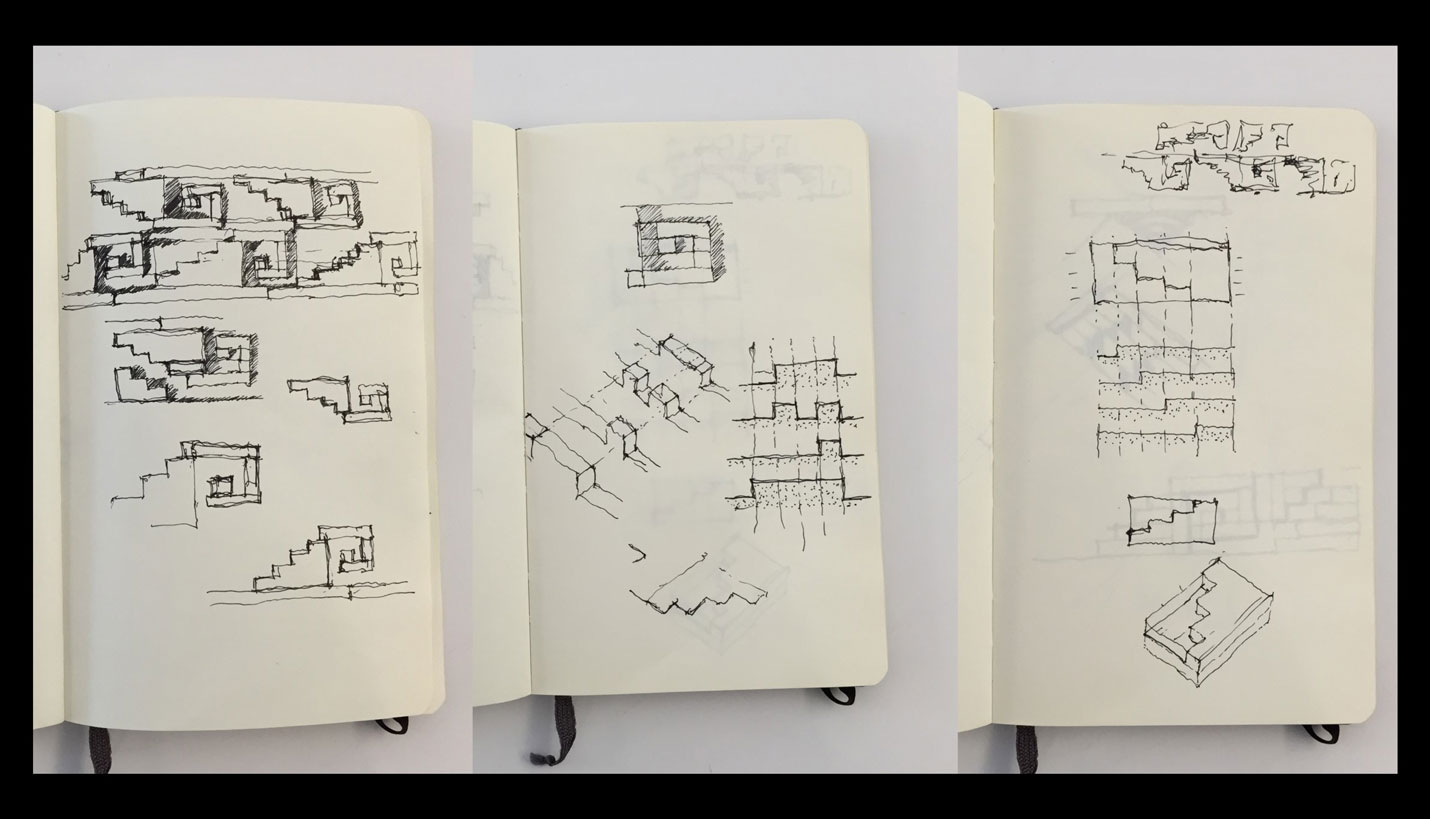

Around the same time I came in contact with Albers’ piece, my studio work began to focus on the “unit” and how one entity regardless of scale could be arranged and organized to create an almost infinite number of unique solutions or assemblies to address certain issues. One of the projects I began was based on a single unique unit the size of a room that was able to flip and rotate to accommodate different conditions impressed upon it. The variety of organizations that were produced from an aggregation of this unit allowed were limitless.

In the same year I was exploring unit structures in my studio, our 1st year class began to work on a large scale installation for an upcoming conference to be held at our university. This installation was to be composed of brick-sized wood blocks into a pair of approximately 10’ tall screen walls. The blocks would be laid by a robotic arm in order to arrive at a precise and exact organization. This process allowed for great accuracy that could not otherwise be obtained by traditional means without detailed measuring, templates or other tedious methods. The final installation resulted in a sinuous pair of walls that were based on the many moves a single unit could produce. The work that I did in studio as well as the large scale class project continued to resonate throughout my graduate career research.

After graduate school I immediately began teaching architecture studios at my alma mater. The first projects I issued to the students were those that again dealt with the idea of a single unit and how it could be propagated to create solutions or to offer ideas on how to address architectural problems. The students responded very positively to the briefs and created beautiful work.

I realized that many of the things I had been working on in school and as an instructor could be applied to my professional work when I started working at Page. The first time I explored the potential of working with a singular unit was on a hospital project in Fort Worth, Texas. The façade for the building expressed the biological nature of the interior program and manifested itself through an intricate pattern of recessed and protruding bricks of differing color. The final product was an award winning building with a façade that expressively articulates the mission of the building through very simple, straightforward and elegant means.

Several years after my first encounter with the work of Albers in Cambridge, I came across an article that discussed the origin of that work and was pleasantly surprised. I learned that in the years leading up to the realization of the brick screen wall in Harkness Commons Albers had visited the ruins at Mitla several times with a fellow artist, Diego Rivera. I began to research this place and found it mesmerizing. I had never heard of Mitla and decided that I needed to visit the place. Shortly thereafter I wrote a proposal to study Mitla and the DCfA awarded me the Swank Traveling Fellowship. I was on my way to Mexico.

I arrived to Oaxaca at the end of October and set out to see as much as I could. The culture and tradition of Oaxaca and its indigenous people undoubtedly were related to the civilization that had built Mitla. I was determined to soak it all in. I stayed in the city for a few days and visited historic structures and plazas and was impressed by the intricate details on and inside buildings and the spatial organization of buildings to create incredible public spaces within the city. These were a great foundation for what I was going to see 40 km outside the city.

The journey to Mitla took less than two hours and I was surprised to see a town had grown around the site. There were disregarded and un-kept Zapotecan ruins amongst the town buildings very close to the official archaeological site. One of the local churches that San Pablo established in 1500s, was even been built atop some of the Zapotecan stone walls. Intricate friezes embedded within those stone walls are still visible on the church exterior.

A few paces from the church one arrives at the entrance to the site of the famous stone buildings and their intricate friezes called the Columns Group and the South Group. Through research I learned that when explorers and archaeologists first started visiting the site much of it was interred and throughout several locations the structures were beginning to fail. The Mexican government entrusted the site to a man by the name of Don Felix Quero to be its caretaker as interest awoke at Milta. The Mexican archaeologist Leopoldo Batres describes the condition of the structures and how a few large, yet manageable stone pieces, had been stolen and were being used in homes around the town. In measuring the sizes of the voids left by the missing stones he was able to identify and locate the missing pieces and replace them in their original location. Batres also added structural elements in certain locations to prevent further decay. He mentioned that he employed steel for these fortifications in order for future generations to be able to distinguish the new from the original.

Visiting the site one notices that there are small underground chambers below several of the large structures. These chambers are believed to have been burial tombs for the Zapotecan royalty and were filled with jewels and belongings meant to accompany the reposing souls. The artifacts in those tombs are said to have been transferred to Monte Alban, the largest pre-Columbian archaeological site in the Oaxacan Valley, by later generations of indigenous people in order to hide them from the arriving European explorers. Perhaps better evidence of the fear of the dismantling of their culture and history is the fact that several of the structures that once made up the complex were destroyed in order to be used as building materials for the church of San Pablo. The intricate stone friezes adorning the walls of the structures are part of the large remaining portions of the complex that are visible. These friezes are composed of individually carved stones held in place by their own weight and the surrounding stone framework. Upon closer inspection one can see the red color that once covered the recessed portions of the friezes, creating greater contrast with protruding elements. The friezes are organized in highly geometric arrangements and each appear to be unique in design. In some locations the patterns appear to repeat, but their construction method differ. In one location a pattern is composed of individual pieces, while a different location may have a very similar pattern carved from larger pieces of stone, but still follows the relief and protruding dimensions of the first pattern. There are two explanations for the origin of the pattern design. One belief is that they are just ornamental patterns and are simply meant to adorn the building faces. The second belief is that they are abstracted interpretations of elements and scenes from everyday Zapotecan life (ocean waves, lightning, the sun, stars, etc.).

It is incredible how such a remarkable jewel of history and architecture has been so well preserved. Don Quero, Mitla’s caretaker, was quoted by USA Consul at Yucatan Louis H Aymé as saying “The big stones are too big, the small stones too small, to move for profit; hence they have suffered little ravage from men.”

Contributed By

Ricardo Muñoz

08/14/2015

People

Related Posts

- The Function of Form in the Millennium

- Leveraging Neuroscience For Focus, Creativity, And Learning

- Dallas Center for Architecture Swank Traveling Fellowship

- Seeing The World Through An Architect's Eyes

- Protecting San Francisco’s Trees

- Empowering Your Career Through Storytelling

- Included In Senior Housing Architecture & Design Awards